Asia-Pacific Forum on Science Learning and Teaching, Volume 17, Issue 2, Article 10 (Dec., 2016) |

Study Design: Talanoa-based participatory action research

Within PSHLP-Tonga, methodologies grounded in Tongan thought and culture are purposefully used to ensure that study methods are centered within a Tongan epistemology. The study used a talanoa-based qualitative participatory action research (PAR) methodology. Talanoa is a communication medium shared amongst Pacific cultures. It is a process of conversation, storytelling, relating of experiences, aspirations and views and listening to different voices within respectful relationships (Halapua, 2008; Vaioleti, 2006). Talanoa allows authentic ideas to be expressed which may lead to “critical discussions or knowledge creation that allows rich contextual and inter-related information to surface as co-constructed stories” (Vaioleti, 2006).

The PSHLP professional development workshops within which the dilemma relating to questioning in Tongan science classrooms arose were also based on concepts of talanoa, emphasizing the importance of voices being heard, and most importantly listening purposefully. The depth to which listening occurs is central to talanoa, and from this emerges communication and dialogue where respect and attention is given to all participant voices (Halapua, 2008). Through talanoa, a safe space is created for dynamic processes supporting critique, from which can emerge evidence-based actions that are appropriate for the social and cultural context. In the case of our talanoa pertaining to scientific and health literacy development, through a process of sharing and listening, reflections emerged that developed into a question, from which the action research reported in this paper has arisen.

A summary of the action-research process is presented in Figure 1. Details of the setting and each component of the methods are described in the paragraphs that follow. The PSHLP study was approved by the University of Auckland Human Ethics Committee (Ref. 011207), the Tonga National Health Ethics Research Committee (Ref. 040614.2). The study was approved by the Director of Education, Tonga Ministry of Education and Training.

Defining the Research Question

The research question emerged within PSHLP teacher PLD examining scientific and health literacies, and their relevance to science education in Tonga. Consensus was sought from the Ministry of Education and Training (MET), participating schools and teachers to investigate the use of questions by teachers within the PSHLP-Tonga study group via teacher observation, an approved research method in the PSHLP project.

Co-construction of the study protocol

Workshop A (3 hours): The Study Design Workshop explored concepts associated with types of questions, use of questions in classrooms, and research methods. A protocol based on the approved teacher-observation protocol was co-constructed. This involved formation of trusted-peer partnerships within the teacher-researcher team; invited observation of a teaching episode; data analysis and interpretation via collaborative workshop. The protocol was confirmed by MET & participating schools.

Data Collection

Classroom observations with a trusted peer.

Teacher-researchers (TRs) self-selected into pairs. Within pairs, one member elected to teach and the other to observe. TR pairs agreed on a time and context for the observation focusing on the use of questions by the teacher in a 10-20 minute episode within a science lesson. The observer recorded questions asked by the teacher and the number of student responses. Both TRs conducted written self-reflections and shared these with each other at a mutually agreeable time. Agreed data was submitted to project lead (PL).

Data Analysis

Workshop B: 4 hours;

Facilitated by the PL the workshop introduced TRs to concepts of qualitative data analysis. A consensus coding criteria evolved from sharing of results of small group coding of anonymized data. This process was supported by the development of coding exemplars via discussion & consensus. The group coding process was repeated until consensus was achieved. Six TRs were elected by the group to summarize the findings.Workshop C: 4 hours;

Facilitated by the PL; 6 elected TRs working in pairs summarized and presented the data analyzed in Workshop B in written formats in preparation for internal peer review.Writing & Peer Review

Workshop D: 2 hours;

Facilitated by the PL and attended by all TRs. The 6TR group presented the findings of Workshops B and C. Peer review discussions involving all TRs were undertaken. These resulted in agreed instructions for the 6TR group to complete development of a research poster and seminar presentation.Workshop E: 1 ½ hours;

Facilitated by the project leader and attended by the 16 TRs. The 6TR group presented the draft poster and seminar. Peer review occurred via small group and then full-group discussion. The 6TR group undertook to make collectively agreed changes.Communication

Seminar presentation:

The 6TR group presented the seminar on behalf of the team. The audience consisted of the CEO of Education, principals and teachers from participating schools. The 30 minute seminar presentation was followed by a response from the CEO and an open discussion. TRs were presented with a certificate of achievement by the CEO of education. A shared meal for the TRs, their families and school/MET leadership provided a culturally appropriate celebration of the achievements of the TR team. Final adjustments were made to the poster presentation via consensus following comments from CEO and Principals. A0 and A3 copies of the poster were distributed to participating schools for use in school-staff discussions. TRs from each participating school gave seminar-presentations to full staff meetings. These were supported by the PL and the school principal. Departmental discussion and planning for actions based on the evidence presented in the seminar followed.Year-end reflections

Annual PSHLP teacher focus groups were used to gather evidence regarding ongoing impact of the action research program.

Figure 1. Study flow diagram

Tonga is a middle-income Pacific Island nation, with a population of just over 100,000, 56% of whom are less than 15 years of age. Approximately 73% of the population reside on the main island of Tongatapu (Tonga Department of Statistics, 2011). The study team consisted of 16 practicing science teachers and one deputy principal from three government schools on the island of Tongatapu, and the project leader. Two of the schools conduct lessons in English, supplemented by Tongan, and one uses Tongan exclusively. Teacher-researchers were strongly supported by the principals of each school. The teacher-researchers all teach science in Forms 1–2/Years 7–8, where students are 11 to 13 years-old. Most also teach science through to Form 5/Year 11. Other than one, the deputy principal and principals supporting the team were not science teachers. Their role was in linking the project to learning and teaching practice PLD in participating schools, ensuring the teachers felt confident that they could try new ideas within the project. The majority of teacher-researchers have a diploma in teaching but have not had the opportunity to undertake university level study in science. This is typical of form 1–5 science teachers in Tonga where only 3% of the population have a tertiary qualification (Tonga Department of Statistics, 2011). The research was the first experience of action research for the teacher-researchers, but not the principals. Teacher-researchers recorded their written intentions, observations and reflections in English. Discussions occurred in both Tongan and English throughout the research process. The project was overseen by the CEO of Education. This leadership gave permission for teachers and schools to openly explore their practice.

Peer-to-Peer (teacher-to-teacher) observation was used to gather data on typical teaching practice with eight of the sixteen teacher-researchers in the project group participating in data gathering as teachers and eight as observers. This process is described in Figure 1. All teacher-researchers were familiar with classroom observation by a principal or deputy principal for appraisal, but peer-to-peer observation was novel. Participating teachers identified a science lesson with a Form 1 or 2 class in which they intended to undertake active questioning with the class-group. Learning intentions were exchanged with a trusted peer who was invited to observe the questioning episode within the lesson and record observations using a standardized observation record sheet. The observer categorized questions used by the teacher as open or closed, recorded the number of students offering to respond to each question, and the number of student questions arising from each teacher question. Student responses and questions were not recorded. Following the teaching episode reflections were recorded by both the teacher and observer independently, prior to meeting to exchange and discuss reflections. Following this meeting final reflections were recorded and development goals set.

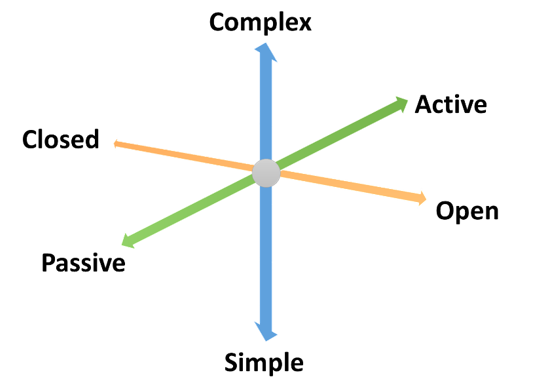

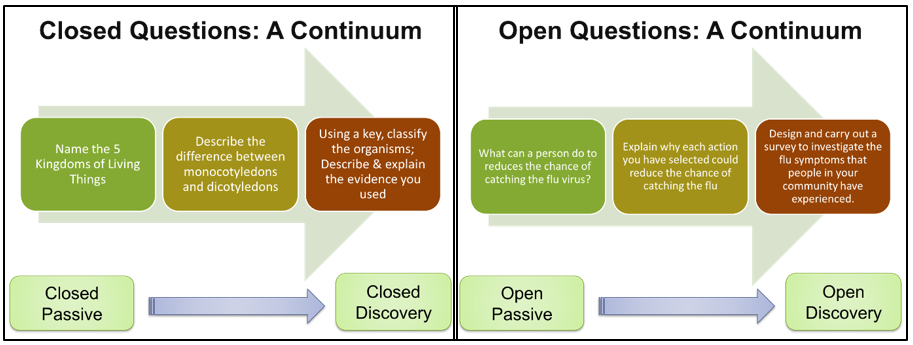

A series of workshops described in Figure 1 were used to introduce participating teachers to qualitative data analysis methods including coding and inter-researcher consistency, a process that was novel to all participating teacher-researchers. Coding was undertaken in small groups to support research capability development in the teacher-researchers. An inter-researcher coding consensus development process during Workshop B was used to establish codes. Groups of four teachers were given anonymized data from two TR pairs and required to code each teacher question as open or closed. Groups were then required to share and justify their coding, initially with one other group, and then with the entire workshop. This process revealed variation within and between groups arising from inconstant conceptions of open and closed questions. Through the talanoa process of open and respectful dialogue, the groups were able to collectively agree on perceptions of open and closed questions, and reach consensus on the coding system. During this process, questions were placed along three continuums, initially in a linear manner, and then within a three-dimensional axis (Figure 2). Open and closed questions were distinguished by the potential for multiple acceptable answers (open) vs defined answers (closed) and cognitive demand (represented by simple to complex in the axis), being greater for open questions (Kawalkar & Vijapurkar, 2013). Within the cognitive demand axis the terms ‘recall’, ‘explain’ and ‘analyze’ were used to categorize questions. The passive to active axis represents the group’s interest in student-centered learning environments, a significant focus of PLD with the project, and a strategic focus within the Lakalaka Policy Framework being implemented in schools at the time of the project (Ministry of Education and Training, 2012). This was not used in the coding process as all questions in the collected data were passive. However, we have included this as it represents the questioning framework that the teacher-researchers aspired to and can be used in future action-research. In developing this coding frame exemplars were established from the data as well as from recent teaching experiences (Figure 3). Notably, once a collection of exemplars was established by the research team, categorization occurred more rapidly.

Coding of reflections was conducted via a constant comparative approach with inductive reasoning (Boyatzis, 1998). A talanoa-based group discussion was used to establish inter-researcher consistency in the manner described above.

All statistical data analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp, 2015). Talanoa followed by peer review were used to support the process of data analysis, writing and seminar presentation development. Themes emerging from the analysis were used to form three hypotheses for future investigation.

Figure 2. Interacting components of teacher-initiated questions identified by teacher-researchers to support coding of questions represented in the data.

Figure 3. Exemplification of open and closed questions on a continuum: used to support teachers in the process of coding of question characterization data.