Asia-Pacific Forum on Science Learning and Teaching, Volume 15, Issue 1, Article 4 (Jun., 2014) |

Historical development of Newton’s Laws of Motion

The meanings and functions of Newton’s original form of laws of motion changed significantly over time. Three stages of the historical development are compared, i.e. (1) prior to the Principia, (2) the final version of the Principia, and (3) a modern view, which is the result of modifications made during the 18th - 19th centuries.[1]

Topics of Newton’s 1st Law (NFL), inertia, force, and Newton’s 2nd Law (NSL), are discussed in sequence following the three stages. Quotes from the literature are supplied to illustrate the meanings of the key terms/concepts.

As noted by Westfall (1980, p.152),

The laws of motion as Newton understood them in the 1660s differed sharply, however, from the laws of motion he pronounced in the Principia (H1).[2]

1. Newton’s 1st Law and inertia

Newton’s 1st Law (NFL) is also known as the Law of Inertia. The statements about NFL found in Newton’s early publication and adapting Galileo’s idea, are translated as, ‘By its innate force every body perseveres in its state of resting or of moving uniformly unless it is compelled to change that state by impressed force… this uniform motion is of two sorts, progressive motion in a right line…and circular motion (Westfall, 1971, p.454) (H2).’

The idea of “innate force” was elaborated as an inherent motive force (impetus) of moving objects, and was referred to as inertia, based on ‘a basic characteristic of matter which we call inertia, … Newton calls materiae vis insita or vis inertiae, or even impetus (Dellian, 1998, p. 228) (H3).’

At this stage, Newton’s ideas regarding NFL and inertia can be summarized as follows: (1) Newton adopted Galileo’s idea of inertia, and referred to it as “innate motive force”, serving as the cause of motion. However, Newton shifted from Galileo’s understanding of inertia as the cause of maintaining circular motion, to the tendency of moving linearly. The Law of Inertia, initiated by Galileo, was based on an idealized “thought experiment” rather than empirical evidence (Schecker, 1992). (2) When innate force (of impetus) was initiated (by Galileo), Aristotle’s notion of motion needing external force was abandoned, which was a crucial mediation to the modern concept of motion (Clement, 1982). (3) The cause of motion was altered from external force to innate force. (4) Newton viewed NFL as applicable to both uniform linear and circular motion.

In the following stages, the functional link between inertia and NFL, the embracing of innate motive force, and the application of NFL to circular motion were overruled, along with the refining of force.

2. Force

In the 1660s, Newton embraced the idea of centrifugal force in order to explain circular motion as “the state of equilibrium” i.e. fulfilling NFL. For example, ‘Newton in the 1660s, like Descartes before him, treated circular motion as a state of equilibrium between opposing forces (Westfall, 1980, p.154) (H4).’ The opposing forces referred to the balance between centripetal force (due to gravity) and centrifugal force.

Therefore, Newton regarded force as both caused by external agents (e.g., gravity) and an inherent entity (i.e., impetus in linear motion, and centrifugal force in circular motion). Newton struggled with the intuitive ideas of innate forces for 20 years before he abandoned them (Steinberg et. al., 1990).

1. NFL and inertia

After 20 years of modifications, in the Principia, Newton modified Newton’s 1st Law (NFL) as ‘Every body perseveres in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed thereon. (Motte’s translation, Galili & Tseitlin, 2003, p.48) (H5).’

The two stages of Newton’s ideas regarding NFL and inertia (H2, H3 vs. H5) are discussed as follows.

(1) The so called “uniform motion” was modified to be limited to rectilinear motion. Circular motion was no longer viewed as applicable to NFL, and the idea of centrifugal force was abandoned.[3]

(2) When defining the meanings of inertia, although Newton discarded the impetus (the innate motive force) concept in the Principia (Steinberg et. al., 1990), he converted it into an inherent force of resistance to change the state of motion (Westfall, 1971, p.442). Both stages consistently regarded inertia as a source of innate/internal force, serving as the cause of NFL. As noted by Westfall (p.449), ‘The inherent, innate, and essential force of a body is the power by which it perseveres in its state of resting or moving uniformly in a straight line…(H6).’

The phrase “force of inertia” had been adopted to illustrate the meaning of inertia (e.g., Cohen & Whitman, 1999, p.404; Dellian, 1998; Westfall, 1971, p.449).

Therefore, the Principia appeared to define dual meanings of inertia as both inherent resistive force in NFL, and mass in Newton’s 2nd Law (NSL). These two definitions regarding inertia are dimensionally inconsistent.

2. Force and NSL

In the Principia, force was adopted in various contexts with discrepant functions and incompatible dimensions, namely (1) impressed force, (2) inherent force, and (3) uniform force.

First, in Newton’s 2nd Law (NSL), impressed force was adopted to intentionally differentiate from “force”, since

(NSL): The change of motion is proportional to the motive force impressed .… Newton’s use of the adjective ‘impressed’ was consciously intended to distinguish mere ‘force’ from ‘impressed force’ (Westfall, 1971, p.452) (H7).

What Newton meant by ‘motion’ was momentum (mv) (Cohen & Whitman, 1999, p.417); thus, in the Principia, the meaning of impressed force was impulse rather than force. In NSL, Newton was actually stating the relationship between impulse (J= F×Δt) and change of momentum (F×Δt=Δmv) rather than force and acceleration (F=ma) (Whitrow, 1971), as argued by Dellian (1998, p.229)

Second law…concerns the proportionality of force and change of motion (mv) stressed by Newton. … force should be proportional to acceleration (H8).

Second, the functional link between Newton’s 1st and 2nd Laws was also provided: (Newton assumed) an interaction between external force (vis impressa) which changes motions, and internal force (materiae vis insita) which maintains motions (Dellian, 1998, p. 228). (H9).

The above statement implies that the original motion (mv) due to internal force (of inertia) can be transferred by means of external (impressed) force to cause change of motion (∆mv). The two types of “force” were both referred to as quantity of momentum, and thus “force” is ontologically viewed as entities (either inherent or transferred), rather than an interaction (Chi et al., 1994).

Third, while impressed force was referred to as impulse (rather than force) in NSL, the condition of NFL: zero force impressed (stated in H5) implied zero impulse (J). Thus, NFL should be interpreted as when J=0, ∆v=0, rather than when F=0, a=0. Therefore, the key ideas of force and acceleration, used in the modern sense (F=ma), remain absent in both NFL and NSL in the Principia.

Fourth, at the same time, uniform force of gravity was explained to the effect of constant acceleration motion, (Fg→ constant a), showing a discrepant effect from those of innate and impressed force, i.e. acceleration vs. velocity. In addition, the ontological assumption of uniform force is interaction rather than entity. In sum, the effect, dimension, and ontological nature of uniform force were disparate from those of the other two types of force. However, while Newton adopted Galileo’s parallelogram sum, he was not aware of the dimensional incompatibility between “forces” of uniform motion (F=mv) and uniform acceleration (F=ma), as noted by Westfall (1971),

Whereas ‘force’ as inherent force causes a uniform motion (F=mv), ‘force’ as centripetal force causes a uniform acceleration (F=ma). Newton’s parallelogram of forces was an adaptation of Galileo’s parallelogram of motions, Newton’s parallelogram assumed that they are identical in their relations to motion (p.435)…. Via the problem of circular motion, Newton’s… conceptualisation of force, uniformly accelerated motion as Galileo’s analysis of free fall presented it. When he took impact as model, Newton had defined force as Δmv… The ambiguity in the definition of force … continued to plague it to the end. (p.355)(H10).

3. Acceleration

Although discussions of “motion and force” can be traced back more than 2,000 years to Aristotle, the idea of “acceleration” was not established until 300 years ago by scientists in Galileo’s age. Regarding Galileo’s invention of acceleration, Arons (1990) noted that

Galileo was explicitly conscious of the fact that he was defining new concepts and not ‘discovering’ objects, (when) he argues about the alternative definitions of acceleration (p.39)… Galileo rejects the former (a=Δv/Δs)… and adopts the latter (a=Δv/Δt) largely because he has the deeply rooted hunch that free fall, … is uniformly accelerated (p.30) (H11).

The constant acceleration of free fall became obvious once the concept of acceleration (a=Δv/Δt≠Δv/Δs), was “invented” (Driver, et. al., 1994).

In the Principia, although Newton referred to average acceleration in discussing centripetal force in planetary motion (Westfall, 1971, p.435), the idea of acceleration was unspecified in either NFL or NSL.

4. Motion and space

Furthermore, in the Principia, Newton adopted an absolute space, explicitly hypothesizing that the centre of the sun is at rest (Westfall, 1971, p. 444). Newton’s view of absolute space contradicts the idea of relative motion implied by NFL, i.e. according to NFL, there is no means to determine the absolute velocity of objects (Whitrow, 1971).

In sum, in the last (3rd) version of the Principia, although Newton had refined the scope of equilibrium (by expelling circular motion), and overcome the intuitive ideas of impetus and centrifugal force, he continued to hold (1) the incompatible force concepts, (2) the dual meanings of inertia, (3) the causal attribution of force resulting in motion, and (4) the contradiction between relative motion and absolute space. The flaws were later amended by Newton’s successors, by means of invention of novel tools (e.g., the inertial frame of reference) and by specifying the meanings of related terms (e.g., force, inertia), as described below.

A modern view regarding Newton’s Laws is summarized, based on both the historical development post Newton’s age and the literature regarding physics pedagogy at introductory university level (e.g., Arons, 1990; Coelho, 2007; Viennot, 2001).

1. NFL, inertia, and inertial frame

Comparing the modern view with Newton’s ideas in the Principia, the meanings and functions of NFL and inertia were modified. When NSL in modern form (F=ma) is valid, NFL becomes a special case of NSL, i.e. since F=ma, when F=0, a=0. Thus, NFL can be held without any cause. Inertia is no longer the cause of NFL, because maintaining original states of motion needs no cause. Viennot (2001, p.53) noted that ‘it is not necessary to seek the continuous action of the cause, because motion can continue without cause (M1).’[4] Therefore, internal resistive force (of inertia) becomes unnecessary for maintaining an object’s original motion (NFL). Steinberg et. al. (1990) contended that the belief that motion requires a causal explanation had become the main barrier to Newton’s long term commitment to perceiving inertia as an innate force of matter. Arons (1990) suggested interpreting NFL to students as ‘rest or uniform rectilinear motion are natural states of objects (M2).’

Since NFL needs no cause, the dual roles of inertia (as they appear in the Principia) turn out to be singular. Inertia is no longer viewed as an inherent force (either motive or resistive) serving as the cause of NFL, but only equates to inertial mass[5], applying to NSL (ΣF=ma). Therefore, the role and meanings of NFL become disparate with the Law of Inertia perceived in Newton’s age.

However, NFL is valid only under the limitation condition of when observed at an inertial frame of reference. Inertial frame becomes a crucial limitation in validating NSL, which will be discussed later. Many researchers have contended that, in the modern view, to make NFL significant as a single law, rather than as a special case of NSL, NFL should highlight its function of providing an operational definition of inertial reference frame (Coelho, 2007; Reif, 1995; Sawicki, 1996).

In sum, in the modern view, inertia no longer serves as the cause of NFL, but refers to mass for NSL, whereas NFL preserves its scientific significance by imparting an operational definition of inertial frame.

2. Force and NSL

In the modern view, the definition of force has been modified more precisely. Since maintaining the state of motion needs no cause, the idea of internal force has been discarded. Force is then ontologically viewed as (1) caused only by external agents, and (2) the interactions between objects rather than as an innate entity of matter. Arons (1990, p. 52) concluded that ‘interactions with other objects are necessary to produce changes in such motion, we can interpret Law 1 as giving the qualitative operational definition of “force”…(M3).’

In addition, for describing both rigid or deformable bodies, the ideas of centre of mass and moment of inertia were proposed by Euler in 1776, leading to the popular formulas ΣF=macom and Στ=Iα, extending the scope, but continuing to be named as Newton’s 2nd Law (Whitrow, 1971). The incompatible dimension between impressed force (N•s) and uniform force (N) was amended, and the effect of force was unified to the change rate of motion (F=Δmv/Δt). The idea of instantaneous acceleration became crucial in the modern form of NSL (F=ma), which was not specified in Newton’s publications.

Furthermore, in the 19th Century, Lord Kelvin devised the tool of inertial reference frame to enhance the validity of NSL (Whitrow, 1971). The initiation of inertial frame also overcame the logic flaw between absolute space and relative motion which appeared in the Principia.

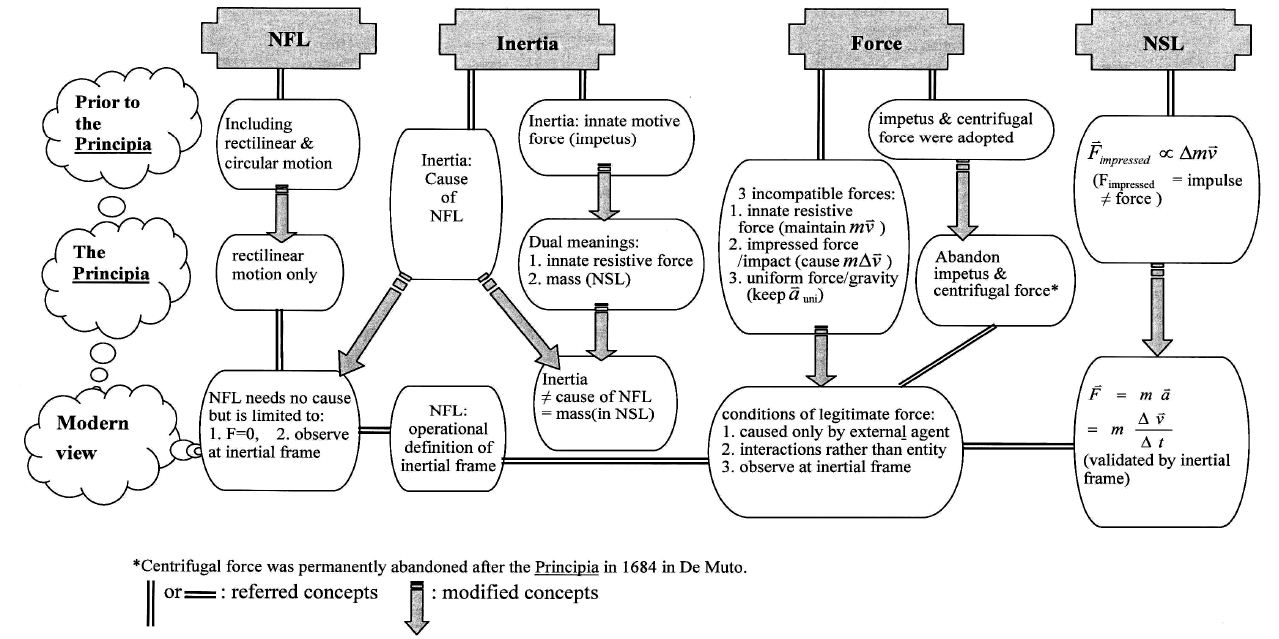

In conclusion, the meanings, functions, causality and limitations of the related terms in Newton’s Laws, e.g. NFL, inertia, force, and NSL, were dramatically modified before, during, and post Newton’s age. A summary of the key modifications as described above is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Historical development regarding the key terms/laws of Newton’s Laws of Motion

The vertical paths of Figure 1 indicate the modified concepts through different periods of time. For example, “inertia” was modified from “innate motive force” to “innate resistive force” in Newton’s age, with both serving as the cause of NFL. Then, the modern view regards “inertia” as mass specifically, since the causal link between inertia and NFL is no longer needed. In addition, the horizontal rows show the concepts and links amongst them at each period of time. For example, the bottom row, the modern view, shows better integration amongst the related terms than the previous two stages. In the modern view, NFL serves as an operational definition of inertial frame, which helps to define “what counts as force”. In the right hand column, the refined definition of force enhances the validity of NSL.

The above discussion has described the historical modifications of the meanings and functions of key terminologies, the invention of scientific tools, and the alteration of the structure of these terms and tools. Thus, in line with Sutton’s (1996) argument, a new scientific model involves a change in the meaning of words in order to see and interpret the phenomenon differently.

[1]The “modern view” adopted in this article is limited to “classical mechanics”, which does not include Einstein’s Relativity. The exclusion of Relativity in teaching Newtonian Mechanics fulfills the curricula of most introductory physics courses at secondary and tertiary levels.

[2]For ease of reference in the following discussion, each quote is coded with H1~H11 the historical notions up to and including the last (3rd) version of the Principia.

[3]The idea of centrifugal force remained when discussing rotating liquids in the Principia. The idea was permanently abandoned in 1684 when Newton wrote De Motu (Steinberg et. al., 1990).

[4]Each quote expressing the Modern view regarding Newton’s Laws is coded from M1~M6.

[5]The discussion is limited to classical mechanics, thus no differentiation is made between inertial mass and gravitational mass. “Mass” defined by Newton in the Principia is ‘Quantity of matter is a measure of matter that arises from its density and volume jointly.(Cohen & Whitman, 1999, p. 403)’