Asia-Pacific Forum

on Science Learning and Teaching, Volume 14, Issue 2, Article 10 (Dec., 2013) |

This exploratory study employed a mixed method design, specifically validating quantitative data model (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007). This design was selected to “validate and expand on the quantitative findings from a survey by including a few open-ended qualitative questions” (p. 75). We developed a survey comprised of 11 pictures of different marine organisms with three associated questions for each (Figure 1).

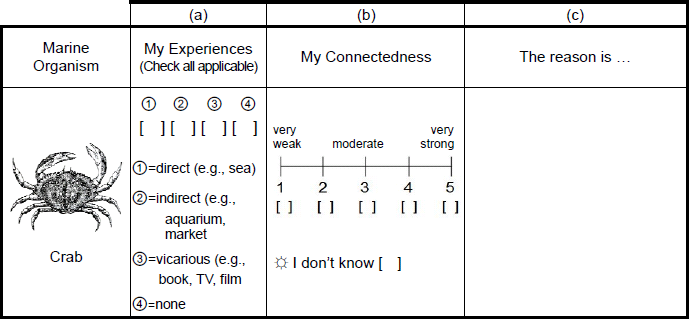

Figure 1. A sample question of the questionnaire.

The marine organisms listed in the survey include: dolphin (representing mammalia), sea gull (aves), sea turtle (reptilia), salmon (osteichthyes), crab (crustacea), sea star (asteroidea), sea worm (polychaeta), sea anemone (anthozoa), jellyfish (or jellies, representing hydrozoa), and sea lettuce (chlorophyta). Several species of plankton (chaetoceros, coscinodiscus, skeletonema, and copepod) were included as one group to represent micro marine organism. We selected these specific marine organisms because they are relatively familiar to elementary students and/or common to the Korean marine environment. The one exception was the sea turtle. Many sea turtle species are endangered and not common in the Korean marine environment. However we included this animal in the survey to understand the students’ perceptions of a diverse group of marine organisms.

In Figure 1, part (a) of the survey was designed to check the students’ different types of experiences with given marine organisms in keeping with Kellert’s (2002) experiential categories. Direct experience was explained to the students as encountering marine organisms in their natural habitats (e.g., live crabs under the rocks in the beach) while indirect experiences was explained as encountering marine organisms in non-natural habitats (e.g., crabs in the market). Also vicarious experience was explained as seeing marine organisms mediated by books or Internet (e.g., pictures of crabs in the storybooks). In part (b), the term ‘connectedness’ was explained as “the degree of association with each organism biologically, ecologically, emotionally or experientially”. In an attempt to help the students understand this term, sample descriptions were provided. The students’ awareness of their connectedness with the marine organisms was evaluated using a five-point Likert scale with “1” indicating a very weak connectedness and “5” for very strong connectedness. The option of “I don’t know” was also provided for students who were unsure about the extent of their connectedness. Part (c) provided the students with a space to describe reasons why they chose a certain degree of connectedness with the given organisms.

The newly developed questionnaire was reviewed by the author team and sent to an elementary school teacher who has a Ph.D. degree in science education and teaches grade 6 science in Seoul, Korea with the intent to check the questionnaire’s construct validity. The teacher was requested to (a) consider whether the items for each marine organism would capture the specific aspect of students’ perceptions of relationship with marine plants and animals, (b) point out any word that might not be clear to Korean students, and (c) evaluate appropriateness of a sample answer for the open-ended question. The teacher’s review led to the modification of some words prior to field testing. The same teacher was also asked to pilot-test the questionnaire with her students (grade 6, age of 13, n=10). The questionnaire was further refined through discussion with the teacher, and several vocabulary terms were changed.

As this was an exploratory study, purposive sampling was adopted. We selected sixth grade Korean elementary school students (13 years old) as this age is a critical period for an individual to develop a relationship with the natural world (Sobel, 1993). It was also our intention to select students with an average level of academic achievement, who came from middle class families, and were residents of Seoul (a highly urbanized city accommodating 10.5 million people, and approximately two hours drive distance to the ocean). Three Korean elementary schools in Seoul were contacted to recruit student volunteers to participate in the research project.

The purpose of the project was explained to both school principals and teachers. The two elementary schools that agreed to participate were sent (1) cover letters, (2) consent forms, and (3) hard copies of questionnaires with stamped return envelopes. All materials including the questionnaire were written in Korean language script. Three classes (grade 6) from each school were invited to join this study. The science teachers in each school were asked to explain the consent form and distribute the questionnaire to their students during regular class time. The students were also asked to submit his/her questionnaire as well as assent/consent forms in a sealed envelope to the science teacher who then collected and mailed them to the researchers. A total of 104 copies of the questionnaire were distributed to the students and 81 copies (42 girls, 52%; 39 boys, 48%) were returned to the researchers for analysis.

Based on the self-reporting questionnaires, the 81 students’ previous experiences with given marine organisms were analyzed through frequency counts. The students’ average connectedness scores with each organism were calculated from their responses recorded on the five-point Likert scales. Responses checked as “I don’t know” were eliminated and treated as missing values. Lastly, the reason why students chose a certain degree of connectedness, via their written responses, were coded using a priori codes list (Table 1) generated from Biophilic Typology toward wildlife (Kellert & Westervelt, 1983). The coded qualitative data were transformed to quantitative data through frequency counts, where each written response in part c) for each of the 11 organisms on the questionnaire was coded for all 81 students. A total of 446 responses were available for coding and subsequent analysis, since not every student gave a reason for why they rated “connectedness” the way they did and ascribed value via their biophilic typology. Two kinds of analyses were performed. First, an overall descriptive assessment of all students’ ascribed values of all marine organisms in terms of their Biophilic Typology. Second, a description of students’ most dominantly held biophilic values for each of the 11 marine organism examined by the questionnaire.

Table 1. A Priori Codes List for Valuing Marine Organisms

Term

Code

Definition

Naturalistic

NAT

Students view the marine organisms based on personal interest, curiosity, and a sense of wonder.

Ecologistic

ECO

Students view the marine organisms focusing on entire system (i.e., humans as a part of ecosystem)

Humanistic

HUM

Students view the marine organisms based on personal affection for individual organisms with strong anthropomorphic association.

Moralistic

MOR

Students view the marine organisms based on ethical concerns for the wrong treatment.

Scientific

SCI

Students view the marine organisms focusing on interest in physical attributes and biological functions.

Aesthetic

AES

Students view the marine organisms based on interest in the physical attractiveness and symbolic characteristics of marine organisms.

Utilitarian

UTL

Students view the marine organisms based on interest in humans’ practical needs.

Dominionistic

DOM

Students view the marine organisms based on interest in the mastery and control of marine animals.

Negativistic

NEG

Students view the marine organisms based on an active avoidance of animals due to dislike or fear.