Asia-Pacific Forum

on Science Learning and Teaching, Volume 14, Issue 2, Article 2 (Dec., 2013) |

The data was collected and then processed in response to the research. This research study identified gaps by comparing the differences and similarities of indoor and outdoor learning in terms of its impact on students’ academic performance in learning science among a total of 24 Grade 3 students and also explored the students’ perceptions towards both forms of learning.

The Wilcoxon test, which refers to either the Rank Sum test or the Signed Rank test was used to compare the two paired groups. The test essentially calculated the difference between each set of pairs and analysed the differences. The Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used to test the null hypothesis that two populations have the same continuous distribution. The test as the nonparametric equivalent of the paired student's t-test was used as an alternative to the t-test as the population data did not follow a normal distribution. The purpose was to analyse the relationship between indoor and outdoor learning in improving students’ performance in understanding science by investigating the degree of complementary of both types of learning. This was performed for both the samples of Grade 3 students from Class A and Class B, each with twelve students who were present throughout the entire research process to maintain consistency in data collection and analysis. Further, pie chart and tables are used to present clear qualitative results of students’ perceptions toward indoor and outdoor learning.

As mentioned earlier, quiz tests were given to the sample of this study to tackle the first and second research questions. The answers to the quiz tests were then graded. Their marks were then tabulated and analysed by using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. The purpose of collecting these data was to investigate the connection of the two types of learning to improve students’ academic performance in learning science. The data was also organised in two simple tables differentiating the total marks out of 15 marks after they have experienced both the indoor classroom science lesson and school excursion as part of the outdoor learning.

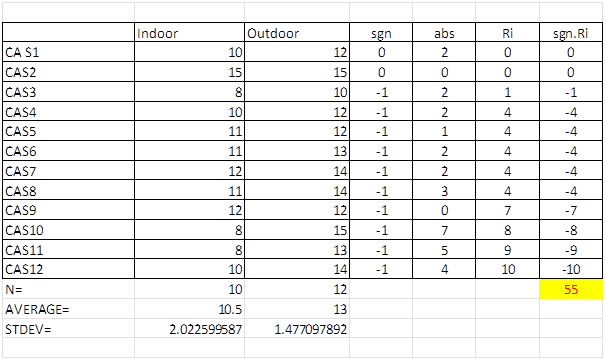

Figure 2. Wilcoxon test (Class A)

Figure 2 shows the Wilcoxon results of Class A. There are two variables in this study indicating the two types of learning. Variable 1 (Indoor) indicates the total individual marks of the first sample, 12 students from Class A, after they had learned an indoor classroom science lesson on man-made structures and its materials with the same learning objectives with that of the outdoor learning. On the other hand, Variable 2 (Outdoor) indicates the total individual marks of the first sample after they had participated in the school excursion as part of the outdoor learning. The Wilcoxon T test resulted in a value of 55 which is compared to be more than the critical value of 14 for 12 data as given in [1]. This clearly suggests we have to reject the median difference between the results obtained after the indoor lesson and outdoor lesson test marks is zero. Hence we can conclude there are differences in marks between the two tests conducted. Based on the marks obtained by the students, the test conducted after the outdoor lesson yielded better results compared to the test carried out after the indoor lesson.

[1] http://www.sussex.ac.uk/Users/grahamh/RM1web/WilcoxonTable2005.pdf

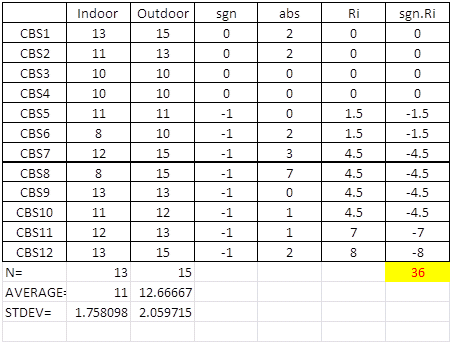

Figure 3. Wilcoxon test (Class B)

Figure 3 shows the Wilcoxon test results of Class B. The Wilcoxon T test resulted in a value of 36 which is compared to be more than the critical value of 14 for 12 data as given in [1]. This clearly suggests we have to reject the median difference between the results obtained after the indoor lesson and outdoor lesson test marks is zero. Hence we can conclude there are differences in marks between the two tests conducted. Based on the marks obtained by the students, the test conducted after the outdoor lesson yielded better results compared to the test carried out after the indoor lesson.

Hence, this confirms that indoor and outdoor learning complement each other to improve students’ academic performance in science. It also justifies the findings of Malone’s (2008) report that learning experiences in both indoors and outdoors are essential as they also expand the range of active learning opportunities available to stimulate imagination and creativity among students. Not only that, Bruce (2010:61) comments that ‘the indoor and outdoor environments should complement rather than duplicate each other’ as she believes that different learning objectives can be best achieved in the provision of different learning environments in various subjects. Complementary to this, Wardle (2004) also shows the importance in constructing active and deep learning of science than just a short-term learning of unconnected facts and concepts for students in both indoor and outdoor learning environments.

Besides that, as the first response to the research questions, this paper has confirmed that both types of learning have impact on students’ academic performance in science. These data findings support distinctly the argument of many educators who support the notion of the impacts of outdoor learning in improving students’ academic performance in science (Jeffery, 2006; Bruce, 2010; Duschl et al., 2007; Hayden, 2012; Fägerstam, 2012; Abell and Lederman, 2007). Conceptual development in science occurs naturally as a product of the child’s learning experiences in the outdoors and subsequently, improving the progressive development of their scientific skills (Duschl et al., 2007; Farmery, 2002).

Nonetheless, there is a number of students in both samples that have achieved the same total individual marks when learning both in the indoors and outdoors unlike the other students. Table 1 and Table 2 show the results of the total individual marks of six students who obtained similar marks in their quiz tests from Class A and Class B respectively.

Table 1. An excerpt of Class A’s Students Quiz Test Individual Marks

Class A

Total Number of Students: 12

Individual Marks

(Full Marks: 15)

Numeric Coding of Students

Pre-Quiz Test

(After Indoor Learning)

Post-Quiz Test

(After Outdoor Learning)

2

15

15

9

12

12

Table 2. An excerpt of Class B’s Students Quiz Test Individual Marks

Class B

Total Number of Students: 12

Individual Marks

(Full Marks: 15)

Numeric Coding of Students

Pre-Quiz Test

(After Indoor Learning)

Post-Quiz Test

(After Outdoor Learning)

22

10

10

23

10

10

24

11

11

28

13

13

Based on the findings in Table 1 and Table 2, it can be argued that both indoor and outdoor learning have relatively equal impact on these students’ academic performance in understanding science. This supports the viewpoints of several researchers who believe that both types of learning may actually impact students in the same manner due to their similarities and few presumably influential factors like dissimilar students’ learning intelligences and the effectiveness in the delivery of scientific instructions (Wilson, 2006; Edlund, 2011; Shih et. al., 2010).

One of the similarities of both indoor and outdoor learning is that they offer the same opportunity for students to be managers of their own learning and the depth of their learning is profoundly determined by students themselves when they make connections of what they observe and learn (Wilson, 2006). By taking charge of their learning, students would have different levels of interest and thus, affecting their attention time span level in engaging with the indoor and outdoor lessons. Since this research study also employed two different teachers for the indoor and outdoor lessons in Class A and Class B respectively, it must be conceded that students may be affected by the delivery of learning and instructions during lessons. This is supported by Wilson’s (2006) idea that the diversity and versatility of learning and teaching approaches in giving scientific instructions in both indoors and outdoors affects the learning process of students.

In general, all students possess different learning intelligences and preferences in understanding science (Farmery, 2002). Students would then acquire important scientific skills such as observing, measuring, recording, drawing conclusions and communicating results at different pace too (Farmery, 2002). These six students could probably be stronger in different intelligences than that which was catered for during the indoor and outdoor lessons about man-made structures and its materials. Along these lines, this paper also recognises that Student 2 in Class A is the only student that achieved full marks for both indoor and outdoor learning. This paper views Student 2 as one who is perhaps a very flexible and responsible student full of curiosity that possesses strong multiple intelligences that aids him/her in learning science.

Survey questionnaires were given to both the samples of this research study to discover their perceptions toward both indoor and outdoor learning in understanding science. The questionnaires contain five questions that were designed to tackle the research questions of this study. Pie chart and tables are used to present clear qualitative results of students’ perceptions toward indoor and outdoor learning in advancing students’ academic performance in learning science. Four teachers were involved throughout the research process playing the role of facilitators of both indoor and outdoor learning. All four teachers wrote their reflection on different aspects of the lessons in the classroom observation forms. The findings from these indoor and outdoor classroom observation forms are also discussed where relevant to consolidate the qualitative findings of this research study.

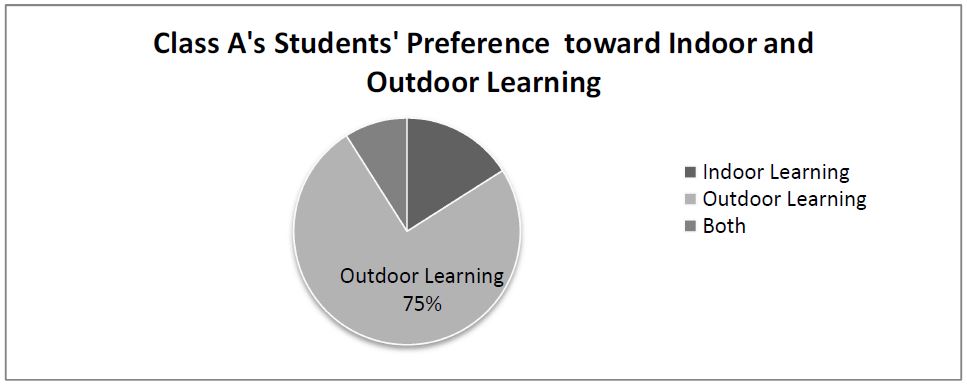

Figure 5. Percentages of Students’ Perceptions toward Indoor and Outdoor

Learning in Class A

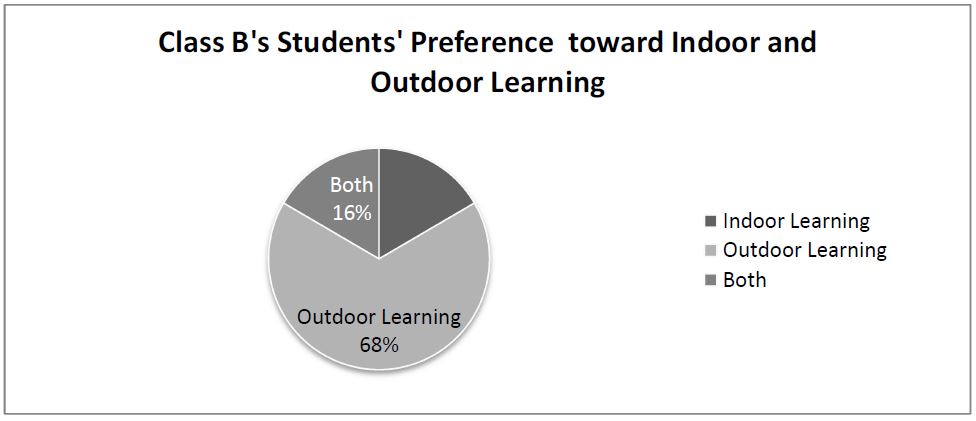

Figure 6. Percentages of Students’ Preference toward Indoor and Outdoor Learning in Class B

Figure 5 and 6 are the tabulation of the responses to the first question posed in the survey questionnaire. Figure 5 shows that a total of 75% of the sample in Class A prefers learning outdoors, 16% indoor learning and 9% both two types of learning whereas Figure 6 shows that a total of 68% of the sample in Class B enjoys outdoor learning, 16% indoor learning and the remaining 16% both types of learning. One significant conclusion that can be made from Figure 5 and Figure 6 is that most students in both the classes enjoy being outdoors for learning science than indoors. Thus, students showed a much more positive response towards outdoor learning in comparison to indoors learning. This is further discussed and illustrated with excerpts of responses to the fourth question posed in the survey questionnaire on the reasons why they enjoy being outdoors to learn science.

Table 3. Excerpts of Class A’s Students’ Perceptions toward Outdoor Learning

Class A

Question 4: Why do you enjoy learning and understanding science outdoors?

Numeric Coding of Students

Students’ Responses

2

We can explore and search for new things we can see outside.

9

We can see more structure and all the view.

11

We can see the real thing.

Table 4. Excerpts of Class B’s Students’ Perceptions toward Outdoor Learning

Class B

Question 4: Why do you enjoy learning and understanding science outdoors?

Numeric Coding of Students

Students’ Responses

24

Because it is very exciting and also very fun when I was learning.

26

Because I get to see more things and learn more things.

28

Because we can listen to birds singing.

Based on the findings in Table 3 and Table 4, students expressed in their own words that they are able to observe and explore the buildings and nature with excitement. This links back to Hayden’s (2012) findings whereby she examines students’ positive responses toward outdoor learning in which they were entirely engrossed in the experience of exploring and discovering the world around them. To add on, the responses in Figure 5 and Figure 6 have also proven that outdoor learning has enhanced students’ enjoyment and this is similar to the findings of previous research (Jeffery, 2006). Students are also making connection of their science learning through sensory learning experiences which are readily available in the outdoors (Bruce, 2010). Student 28 in Class B expressed his/her feelings that he/she can listen to the birds singing while Student 9 in Class A expressed that he/she can see more structures and get a complete view. This paper agrees with Edlund (2011) that such responses are significant indicators of the power of the natural environment as a perpetual and dynamic stimulator for sensory exploration and creative expression in learning science.

On the contrary, there is a lesser percentage of 16% in both classes for those who prefer staying indoors to learn science as illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The reasons given by the samples are shown in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5. An excerpt of Class A’s Students’ Perceptions toward Indoor Learning

Class A

Question 4: Why do you enjoy learning and understanding science indoors?

Numeric Coding of Students

Students’ Responses

3

We see many things and do many things.

10

Because we can explore more.

Table 6. An excerpt of Class B’s Students’ Perceptions toward Indoor Learning

Class B

Question 4: Why do you enjoy learning and understanding science indoors?

Numeric Coding of Students

Students’ Responses

21

Because it is fun.

27

Because we can learn and have fun at the same time.

It is interesting to note that the responses given by students who prefer to learn indoors as described in the excerpts are almost similar to those who picked outdoors as their best option. These responses are in consensus with Wardle’s (2004) research that was done to prove that rich, indoor environments have the potential to give an instant, positive effect on the quality of students’ learning process. These four students from the two different classes voiced out that they can also observe and explore different things with joy in indoor traditional classroom settings. The quality and diversity of science activities applied in the indoors can broadly affect the on-going classroom engagement and development in learning (Wardle, 2004). All 24 students in this study experienced the same teaching activities that reflect the inquiry cycle of Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning Cycle. The lesson began with a Word Splash activity to test their prior knowledge on man-made structures, short videos on how different materials are used to make a structure, hands-on activity by using different materials to create their own structure followed by a slideshow presentation and ended with reflection time to summarize their learning.

Furthermore, both the classrooms were equipped with several resources and materials to support the learning of science such as library books, science corner and classroom displays. The classrooms were also well-maintained and thus, gave good vibes for students to learn and participate in classroom-based activities. To elaborate further, the researchers agree with previous research findings that have proven that active, engaging learning can still take place in the indoors by bringing in some constructive traits that are subjected to expressive learning and playing experiences (Greenman, 1988 as cited in Wardle, 2004). Since students spend most of the time in the classroom, they automatically love the learning that takes place in the traditional classroom setting and show the willingness to engage enthusiastically in the classroom activities too as they feel comfortable (Reid, 2007). Plus, students who have a strong intrapersonal learning intelligence will definitely enjoy being indoors than the outdoors as they are independent learners.

Another finding that the researchers would like to highlight is the students who chose both types of learning as their preference in understanding science. The findings are shown in Table 7.

Table 7. Responses from students who preferred both types of learning

Numeric Coding of Students

Responses

12

‘We need to have something new every lesson’

21

‘Yes, you can never do everything every day because you need to try something new’

These two students revealed their viewpoints on the rationale of selecting both indoor and outdoor learning as being part and parcel of their science learning. The combination of both types of learning in science lessons are important as it can provide a wider range of new learning activities to be executed in and out of the classroom. In the same way, the diversity and versatility of learning and teaching approaches can be adopted in both indoors and outdoors to accelerate the learning process for students (Wilson, 2006). Likewise, it is also agreed by many educators around the world that both learning environments are tailored for the main purpose of educating students effectively in terms of their knowledge, understanding, skills and attitudes (Wilson, 2006; Reid, 2005; Brown, 2004).