Asia-Pacific Forum on Science Learning and Teaching, Volume 16, Issue 1, Article 3 (Jun., 2015) |

Few significant differences between genders

Several between-class analyses showed significant differences (p-value<0.005) among groups defined by some instrumental variables: countries, gender, groups of teachers (primary school teachers, and secondary school subject teachers of biology and language), levels of qualification and religions. The gender effect was significant for Swedish sample, French sample and for Swedish plus French sample. Nevertheless, after suppression of other significant effects (PCAIV), gender effect was no more significant for French sample. It was still significant for Swedish sample (p-value<0.005), but only from responses to questions A12 and A56a (Table 1). It was also significant for Swedish plus French sample (p-value<0.005), but only from responses to questions A56a and A78 (Table 1). Thus, of the 41 questions analysed in this respect of multivariate analyses, only responses to three questions showed significant differences.

The above results show that female and male teachers differed to a low extent in their pro-environmental behaviour, conceptions and attitudes towards nature and the environment. Nearly the same absence of gender difference emerged from univariate analyses within Swedish, French and Swedish plus French samples. Only three of the 41 questions (A12, A56a and A80) showed significant differences (p-value<0.005) between female and male teachers (Table 1). The significances were seen in Swedish sample (A12, A56a) and Swedish plus French sample (A56a, A80).

Significant differences in responses from women and men were thus found only for four questions (A12, A56a, A78 and A80; Table 1). Only two of the comparisons, where women to a significantly greater extent than men answered that nature should be preserved (A78) and that nature is pleasant (A80), could be interpreted as support for ecofeminism. The other two significant differences (A12 and A56a) could be interpreted as challenging ecofeminism, as women and men did not answer according to what could be expected from an ecofeminist perspective. Responses to questions that could be interpreted as support for ecofeminism were found in categories Attitudes (A80) and Ecocentric and anthropocentric views (A78), while responses to questions that could be interpreted as challenging ecofeminism were found in categories Genetically modified organisms (A12) and Trust in authorities (A56a).

To summarise, multivariate as well as univariate analyses show that out of the 41 questions analysed, there were no significant differences between answers from women and men for 37 questions. Thus, the vast majority of comparisons between answers from female and male teachers showed no significant difference.

Main difference between countries

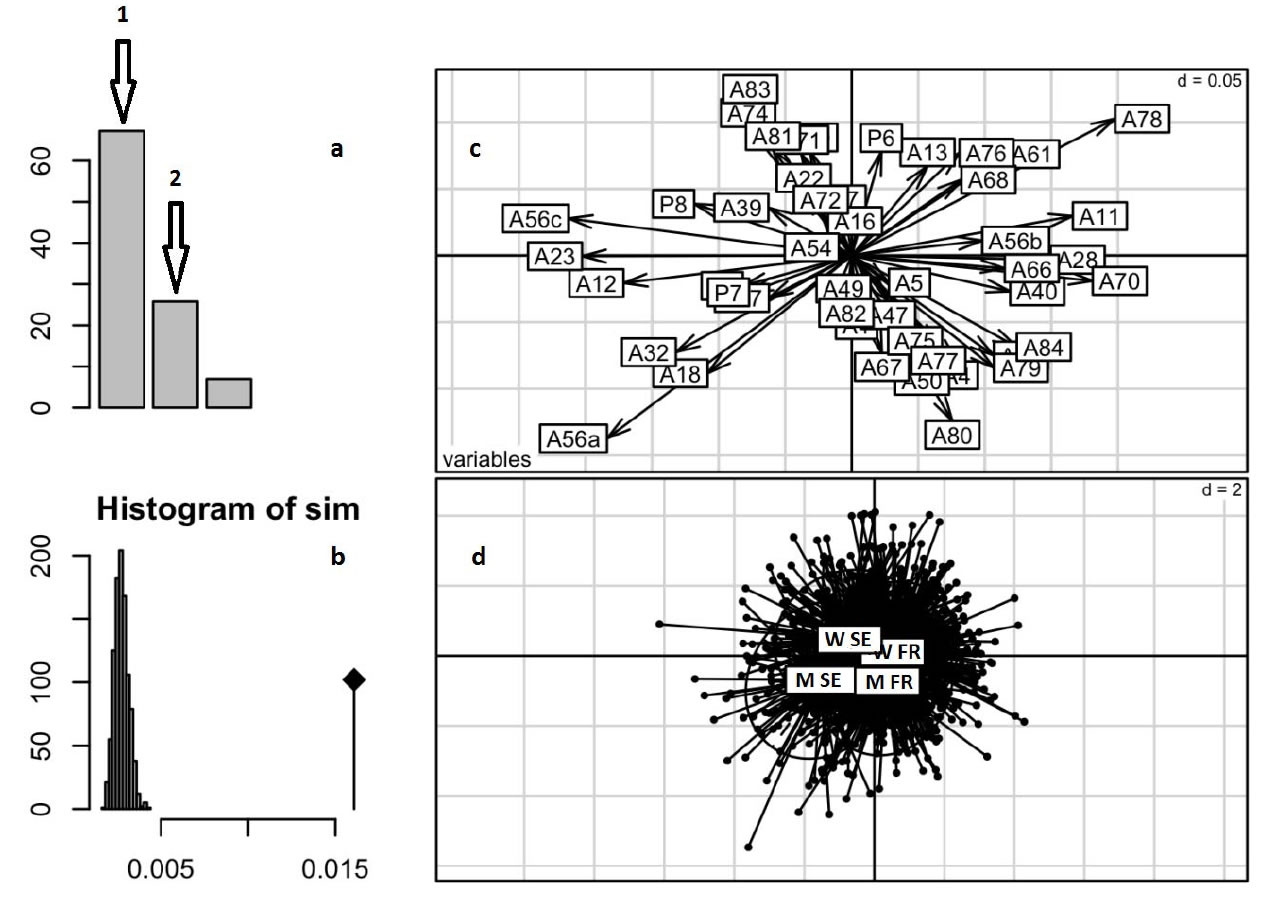

A between-class analysis (Fig. 1) discriminated four groups of teachers, female and male teachers in Sweden and France, respectively. The first component exhibited just under 70% of variance (Fig. 1a), and differentiated between the two countries (Fig. 1d). In this paper, we included no research questions about country differences since those have been dealt with elsewhere. Country differences have been shown for 16 countries (Munoz et al., 2009), however not including Sweden, but we would nevertheless like to point out that country differences between Sweden and France were much bigger than gender differences.

Figure 1. Between-class analysis of Swedish and French female and male pre- and in-service teachers’ pro-environmental behaviour, conceptions and attitudes towards nature and the environment. (a) Histogram showing respective variance of the three components. Arrow 1, the first component (horizontal axis in the graphs at right) corresponds to just under 70% of the total variance, while arrow 2, the second component (vertical axis in the graphs at right) is approximately 25% of the total variance. (b) Monte-Carlo permutation test shows that the observed variance (point at right) is very different from variances obtained randomly (1,000 essays = the histogram at left). (c) Correlation cloud for the 47 variables, showing the meaning of each component: the difference between countries (component 1) and the gender difference (component 2). (d) Overview of all responses: one point for each teacher’s conceptions and attitudes relative to the centre of gravity for the four classes of W SE (women Sweden), M SE (men Sweden), W FR (women France) and M FR (men France). The horizontal axis shows the difference between the two countries and the vertical axis the gender difference.

The second component, approximately 25% of total variance (Fig. 1a), placed women at the top (Fig. 1d) and men at the bottom (Fig. 1d), which shows that differences between the two countries were clearly greater than differences between women and men.

The difference between the four samples is very significant, as shown by the randomisation test Monte Carlo (Fig. 1b: p<0.001). In Fig. 1c, the correlation cloud is seen for the 47 variables, showing the meaning of each component, suggesting that gender differences (vertical axis) are mainly defined by responses to questions A56a, A80, A83, A74 and A78. Nevertheless, the PCAIV showed (see above) that differences related to questions A83, A74 and perhaps also A80 are more a consequence of other effects than the gender effect.

Results presented here indicate that female and male teachers’ pro-environmental behaviour, conceptions and attitudes towards nature and the environment showed only very little difference. Statistical differences were bigger and more frequent between the two countries than between women and men.